Story by Jane Mahoney

For the Abq Journal – January 10, 2010

Photographs by Greg Sorber

Of the Journal

When the sun rises over Old Town, the soft morning light trickles through a narrow bank of glass-block windows set high in the east-facing adobe wall that defines the bedroom of Lloyd and Jan Garcia.

“You wake up a little easier,” said Lloyd Garcia. The slowed rhythm of a bygone era seems to come naturally in this meticulously restored adobe home, an Old Town residence that’s come close to facing the wrecking ball a few times in a life that dates back 130 or more years.

The old adobe home, with nearly 3-foot-thick walls of terrones and adobe bricks, is getting another go-around thanks to the Garcias and the restorative talents of builder Matteo Pacheco, owner of Lizard King Design and Construction. Pacheco is a self-professed adobe aficionado who found a way not only to save the old walls and beams, but also to create a seamless addition using his favorite building material.

Here, overlooking Tiguex Park in one of Albuquerque’s most historic neighborhoods, this old adobe abode stands proud again with an updated open floor plan that utilizes the original massive adobe walls — most of which had been saved during various remodelings and additions over the past half century or more.

Garcia bought the old home more than 20 years ago, “on a whim,” he says. “It was falling down, ready to be condemned,” he remembers. The new owner did enough basic remodeling (such as tearing out the dirt-insulated ceilings) to live in it for a year as he built a new two-story, frame home on a vacant lot next door. Although he occasionally considered selling the older place, Garcia instead rented it out for the next 20 years.

Garcia and his wife, Jan, took a second lingering look at the old adobe last year. It had, after all, always exuded a certain charm and pull on the couple. “The stairs in the newer house were starting to bother us,” he said. “We talked about finding a one-level home. Truth is, we’ve come to love this neighborhood.”

Pacheco’s adobe skills — and his ability to work with constantly evolving plans and changes made on the fly — proved irresistible. The Garcias moved into the old adobe in early December after six months of restoration work that nearly doubled the size of the old 1,000-square-foot home.

Neighbors came to watch and share stories while the Lizard King demolition crew stabilized the foundation, tore out layers of linoleum and carpet that covered rotted floor boards, created arched pass-throughs where windows once stood, and built thick-walled additions with new adobe bricks.

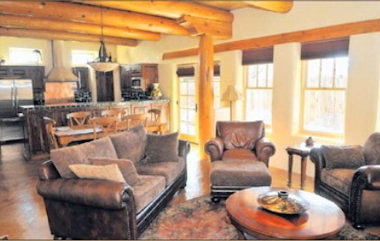

The addition of an open great room combines the kitchen, dining area and a living room. In the new spaces, like the old, massive, rounded New Mexico pine beams and corbels define the ceiling. “We probably spent about two months going backwards,” said Pacheco, the visionary who would often find artifacts from centuries past as he tore up the old floor. On display in the renovated home today are worn spoons encrusted with a rich green patina, a rusted stirrup, a thimble, button and more old treasures.

Along with the artifacts, the Garcias gathered unconfirmed stories. Most likely built sometime between the 1860s and the 1880s, the Garcia home originally was a blacksmith shop, according to neighbors with long generational ties to the neighborhood. The home next door might have been a tack shop, perhaps even a stop on a stage line between Albuquerque and Santa Fe.

Jan Garcia has been told the property was once part of a Jesuit vineyard. Pacheco said a builder’s challenge is to blend the old and new spaces of the home to create smooth transitions that for the most part are unnoticeable. Several elements tie this home together — the diamond-smooth hard plaster that glows with a beeswax finish, and the acid-etched concrete floors that resemble hard-packed clay but instead incorporate the home’s modern radiant heating system.

The thick adobe walls are the heart of this old home, however. While the original renovation plans called for frame wall additions, Pacheco was able to offer an adobe alternative that fit the Garcias’ $200,000 construction budget. Adobe work, he says, generally costs more than framed walls because of the labor involved in laying the courses.

“Adobe gives a wall so much character,” said Pacheco. “It’s all about the gentle curves and the irregularities. As we started, Lloyd asked me, ‘How are we going to straighten all these walls?’ I told him ‘We’re not, we’re keeping them as they are so long as they’re smooth and structurally sound.’” Jan Garcia’s renovation wish list included the creation of deep storage spaces (the original home lacked closets entirely), and the addition of an open great room that combines kitchen, dining area and a living room dominated by a traditional kiva fireplace.

In the new spaces, like the old, massive, rounded New Mexico pine beams and corbels define the ceiling. A courtyard off the bedroom is yet to come.

Unlike the olden days, the new adobe walls have been well insulated with a spray foam insulation that complements the earthy unevenness of the brick walls. A boiler serves the radiant heat system, while cooling can be provided by an evaporative air system if the massive walls, operable windows and shaded overhangs don’t do the trick on their own. New efficient windows, appliances and lighting add a touch of green building techniques to this brown earthen dwelling.

Pacheco, who studied both architecture and art at UNM before starting his design and construction business 10 years ago, has earned the nickname of “the Lizard King”

because of his distinctive 3-D wire, lath, and stuccoed “lizard” sculptures that wrap around the walls of some of his building projects both new and old.

The Garcias, meanwhile, relish the solitude furnished by the thick, earthen walls that bring the added benefit of reducing noise in this active part of the city surrounded

by museums, shops and parks. “We don’t hear anything in here,” said Lloyd Garcia. “We love the feel of this old home – it’s strong, sturdy, secure, and absolutely quiet.”

Copyright (c) 2010 Albuquerque Journal, Edition 1/10/2010